Welcome to the PWP Corner’s section on Worry Management.

The PWP Corner is designed for therapists. If you are not a therapist try looking at my self help section instead.

This section has two parts:

2) Information on how to guide a patient through Worry Management.

Worry Management Worksheets:

These are free to use worksheets you can use with your patients.

Click the image to download the worksheet.

ABC Cycle:

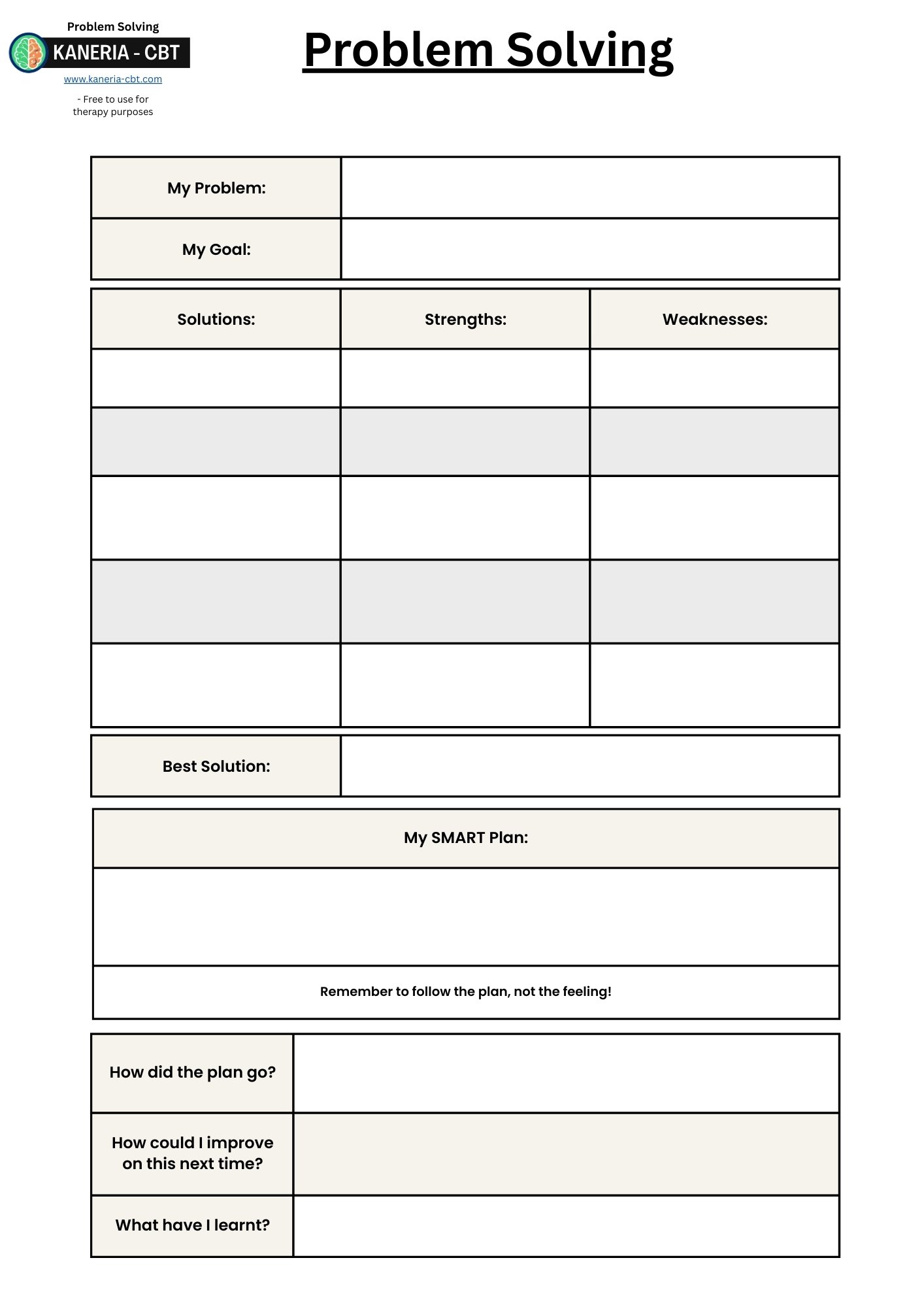

Problem Solving:

Five Areas:

Worry Cycle:

Worry Diary:

Worry Management Guide:

Worry Management is a very simple but highly effective strategy for overcoming chronic worrying.

The main rationale for what maintains anxiety is that those with chronic worrying struggle with uncertainty and use the act of worrying in an attempt to reduce this uncertainty. However, this backfires by causing more uncertainty and reducing their tolerance to the unknown over time. This can be come a self reinforcing cycle where the more someone worries, the more uncertainty they actually produce. Therefore, a way to break out of this cycle is to reduce the amount of time the patient spends worrying. This is achieved by postponing worrying about things outside of their control and by the use of effective problem solving for the worries they can solve.

The Main Steps of Worry Management consist of:

Step 2: Worry distinction: hypothetical and practical.

Step 1: Psychoeducation:

Psychoeducation should consist of:

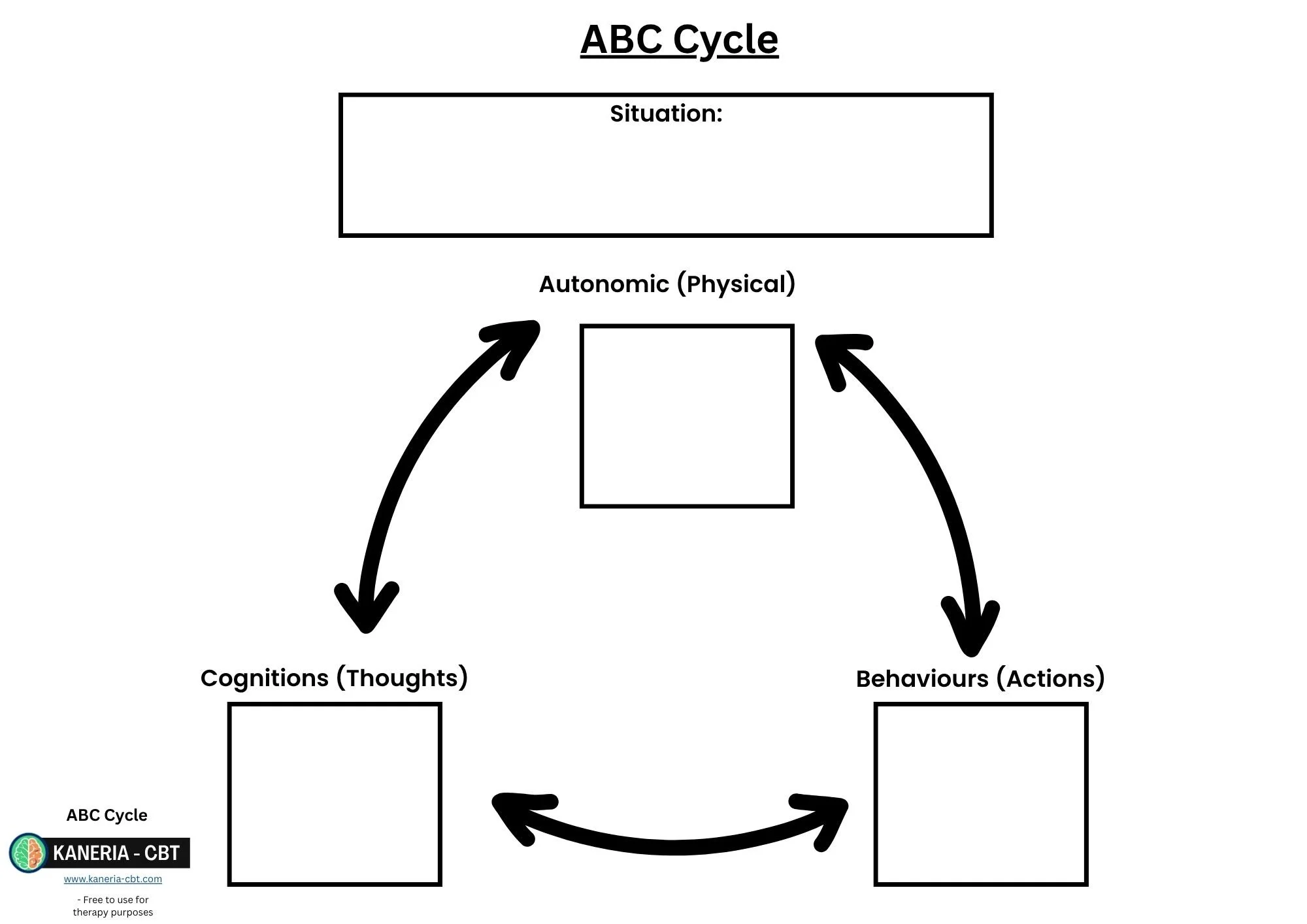

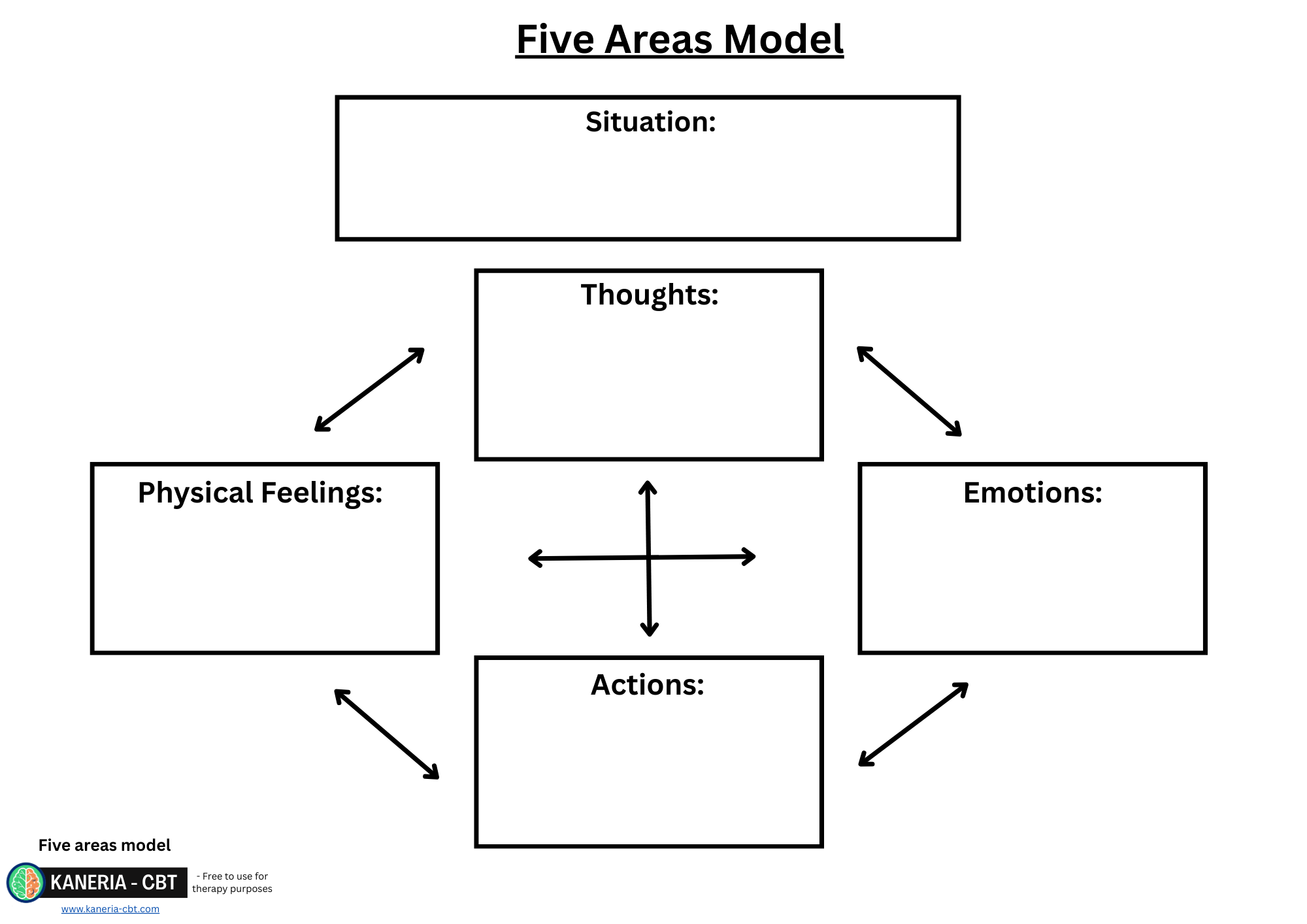

Providing information on the ABC cycle or five areas model and getting the patient to fit themselves into their own cycle.

Some PWP' self-help guides will include information on intolerance of uncertainty and worry behaviours.

Exploring an anxiety maintenance formulation if you feel this is appropriate for the patient.

ABC Cycle or five areas model:

Always start with an ABC cycle or five areas model as usual. These cycles for GAD often involves the patient experiencing a lot of “what if” worries as well as all the usual anxiety autonomic symptoms. Do not spend much time on discussing the actual worries itself, as it's mostly irrelevant to the treatment of GAD. Pay extra attention to the behaviours the patient uses, particularly how long they spend worrying and how they resolved their worry/problem. In terms of behaviours, they can display a wide range of worry behaviours. Being aware of worry behaviours is useful, but the common one to focus on at step 2 is the act of worrying.

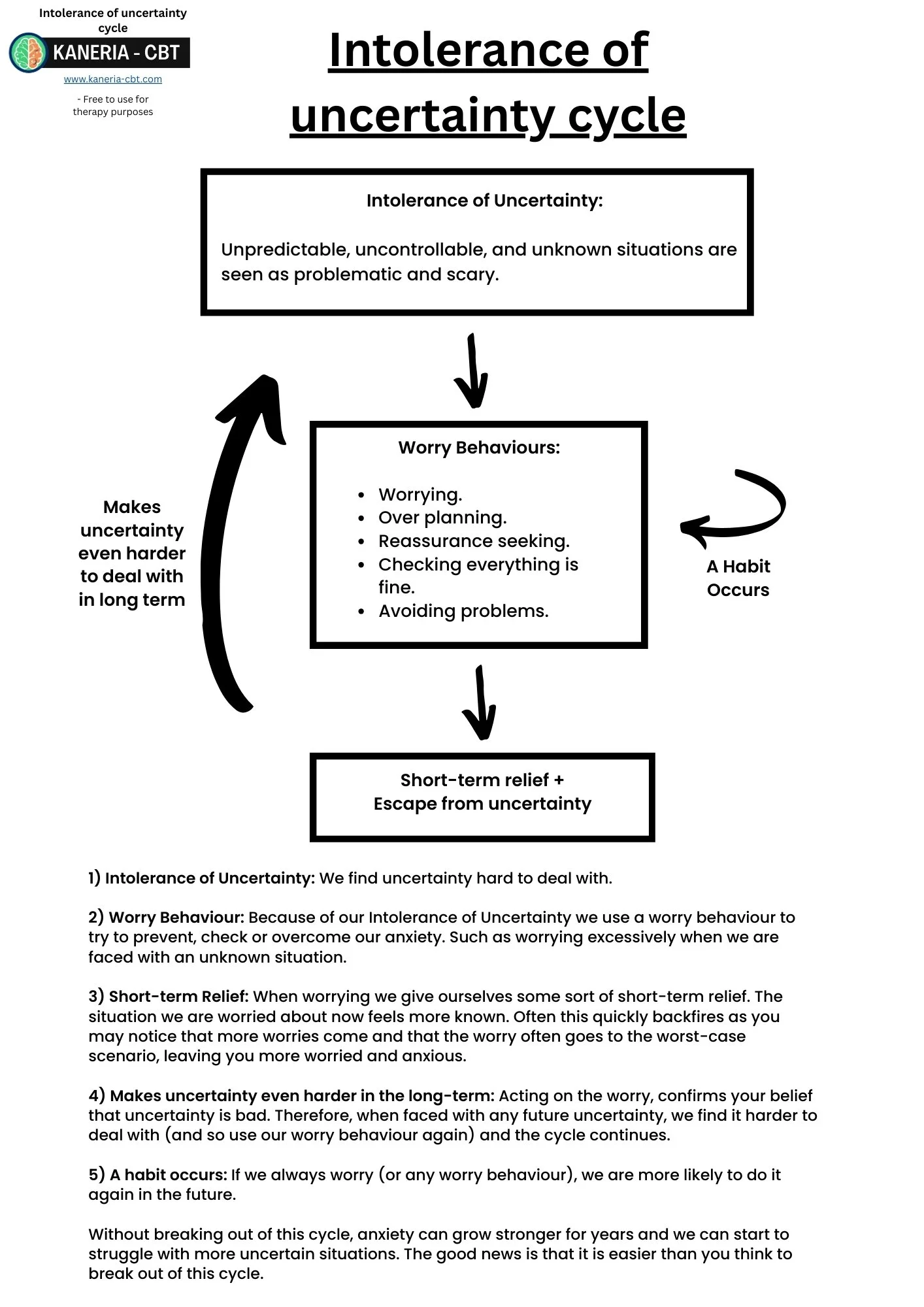

Intolerance of uncertainty and the anxiety maintenance cycle:

It is optional but showing patients a maintenance cycle for depression can be helpful at helping them understand the rationale behind what maintains their anxiety and worrying. This informs how and why the treatment works.

There is no established step 2 model for the maintenance of GAD and many versions exist but they all show similar principles. The version used here I created personally and is based on concepts borrowed from the step 3 intolerance of uncertainty protocol by Robichaud, Koerner and Dugas (2019). See this maintenance cycle as an optional psychoeducation point. Many PWPs do not include this, or even know it themselves. But personally, I have found it very useful to get a patient to understand this, as it allows them to apply their learning to other worry behaviours than just the act of worrying (for which worry management focuses on). Any extra awareness for the patient on their main problem is always a good thing. It also gives them a good rationale for how the “Worry Time” technique actually works.

This cycle is made up of 3 concepts:

1) Intolerance of Uncertainty.

2) Worry Behaviours.

3) Short-term Relief and the reinforcement of intolerance of uncertainty and use of their worry behaviours.

Intolerance of Uncertainty:

Intolerance of uncertainty is where an individual finds uncertain situations scary, hard or intolerable. Everyone has a different tolerance to uncertainty, which changes based on the situation. For example, think of someone who is able to tolerate this highly. They may be able to, on a whim, travel to another country on very little notice and just go exploring. While on the other side a person who does not tolerate uncertainty must plan for months every small detail of a trip. People can tolerate uncertainty differently for different areas of their life; thereby tolerating uncertain situations well and others poorly.

Worry Behaviours:

When facing uncertainty, a patient will feel distressed, anxious and worried. This is where they often start to get “What if'' worries. Due to these feelings and thoughts, they feel the need to engage in “worry behaviours”. These behaviours all attempt to reduce or avoid the uncertainty in the situation but backfire and maintain anxiety in the long term. Worry Behaviours are basically another name for safe-seeking behaviours. These can include:

Spending excessive time worrying: This aims to reduce the uncertainty in one's mind by thinking of all the things that could happen to assess likelihood of what will happen (almost always backfires as this creates more uncertainty for each possible new outcome thought through). People with GAD will often overestimate the likelihood of worries coming true and feel they can not cope if it was to occur.

Avoiding situations: This aims to reduce the uncertainty by simply not letting the bad outcome happen. E.g. you can not get into a car crash if you never get into a car.

Over planning: This aims to reduce the uncertainty by reducing the number of things that can go wrong. Patients with GAD often take pride in their ability to plan. Most are shocked to realise this is actually maintaining their anxiety.

Over researching: This aims to reduce the uncertainty by providing more information and reducing the unknown or uncertain elements. This can backfire if the topic in question has no definitive answer.

Reassurance seeking: This aims to reduce uncertainty by gaining certainty from others. This is often short lived, and the anxiety quickly returns.

Procrastination: This aims to reduce the uncertainty by putting it off this later. In that moment in time, the issue “feels” resolved as it's now a problem for later. This backfires as the issue usually grows larger and deadlines quickly arrive.

Checking: Patients can often check if things are okay. This makes the patient temporarily feel better but often causes them to doubt the thing they check more. They can even start to doubt their own memory. This overlaps highly with OCD, so if in doubt, ensure you take these cases to supervision An example of this: Imagine a patient who worries if their partner is cheating on them. They can check their phone for evidence. If they find nothing, does that reduce their anxiety? It might for a moment. But what about the next day, week or next time they have this same worry?

Not delegating tasks: It can be hard to delegate if you are unsure if someone will do the task right or not. This typically leads to patients taking on more and more responsibilities and stress. And more responsibilities, means more things to worry about.

Distraction: Always having to keep “busy” to stop thinking about the worries. This is usually short lived, and no one can stay distracted forever.

There are many other worry behaviours that exist, but typically the only one we focus on at step 2 is the act of worrying. The idea is that when the patient engaging in worry postponement (worry time) they will also be reducing these worry behaviours as they are instructed to let the worry go until later. If excessive amounts of worry behaviours are present, a step up may be required.

Temporarily Relief:

When a patient engages in these worry behaviours they get a sense of relief. This can be as small as a feeling they have done something to help, to full blown relief (usually when avoiding). The absence of the worry coming true can also be incorrectly attributed to the worry behaviour, reinforcing their use. For example, if a patient worried excessively, and nothing bad happened, they could possibly think it did not occur because they were “ready” or “acted differently”, even if it would not have occurred regardless.

As you can see from all of these examples, reducing uncertainty by using these worry behaviours never works long term. It makes the patient less able to tolerate the uncertainty next time. So, they try to control it again, using more worrying behaviours. Using this model, anxiety is self-reinforcing and without treatment can maintain itself for a lifetime (You have probably heard someone say at some point “I have been a worrier my whole life”). The patient needs to learn to tolerate the uncertainty by not engaging in worry behaviours (in step 2, by stopping the act of worrying).

Full PWP textbook available on Amazon

〰️

Full PWP textbook available on Amazon 〰️

Step 2: Worry distinction: hypothetical and practical.

The next step is psychoeducation about the two types of worries and helping the patient engage in worry distinction. There are two main categories of worries, those which are hypothetical, and those which are practical (Farrand, 2020). Both these worries have directly opposite treatment techniques.

Hypothetical worries are those worries which are outside of the patient's control or that there is no realistic solution. Practical worries are those which the patient has control over or a realistic solution is possible.

Example Hypothetical Worries:

“What if something happens to my partner?”

“Will I lose my job?”

“What if I get Covid?”

“What if I mess up at work?”

“What if I miss the deadline?”

“What if I don't get a parking spot?”

“What if there is traffic and I am late?”

“What if my son/daughter/loved one gets hurt?”

“What if my partner leaves me?”

“What if I make my children anxious?”

“What if my health declines?”

Practical worries are worries for which there is a solution, or practical steps you can and should take towards fixing the problem.

Example Practical Worries:

“How am I going to afford this bill”.

“My car just failed the MOT. How am I going to get to work tomorrow?”.

“I only have £50 left in my bank and it's the beginning of the month”.

“I have a deadline for this form I need to do”.

“I need to cancel my phone contract, but I have been putting it off”.

Mixed worries:

Occasionally patients will have a worry which falls a bit into both categories. In these cases, it can be useful to break down the worry into its key parts to find out which parts are hypothetical and which parts are practical.

Are the solutions realistic:

Often GAD tricks patients into thinking all of their problems have a practical solution when in reality most end up being hypothetical. This causes some patients with GAD to attempt to make hypothetical worries into practical ones.

Let's look at an example to illustrate the point:

Trigger: Patient has to take a plane next week.

Worry: “What if the plane crashes?”

For most people they realise that is hypothetical as they have no control over that situation. But if you really did some unhelpful mental gymnastics, you can find some unrealistic solutions and attempt to make it practical, such as:

1) learn to fly the plane yourself in case the pilot passes out.

2) take a parachute.

3) speak to the mechanic somehow beforehand to make sure it is all okay.

As you can see all of these are unrealistic. Some examples patients may come up with may not be as obviously unrealistic as this. But getting the patient to look at their solutions in terms of realism can be helpful in getting them to realise they are hypothetical.

This can also extend to whether or not the patient is trying to unnecessarily pre-empt a problem before an actual problem occurs. This can be useful for patients who over plan as a worry behaviour.

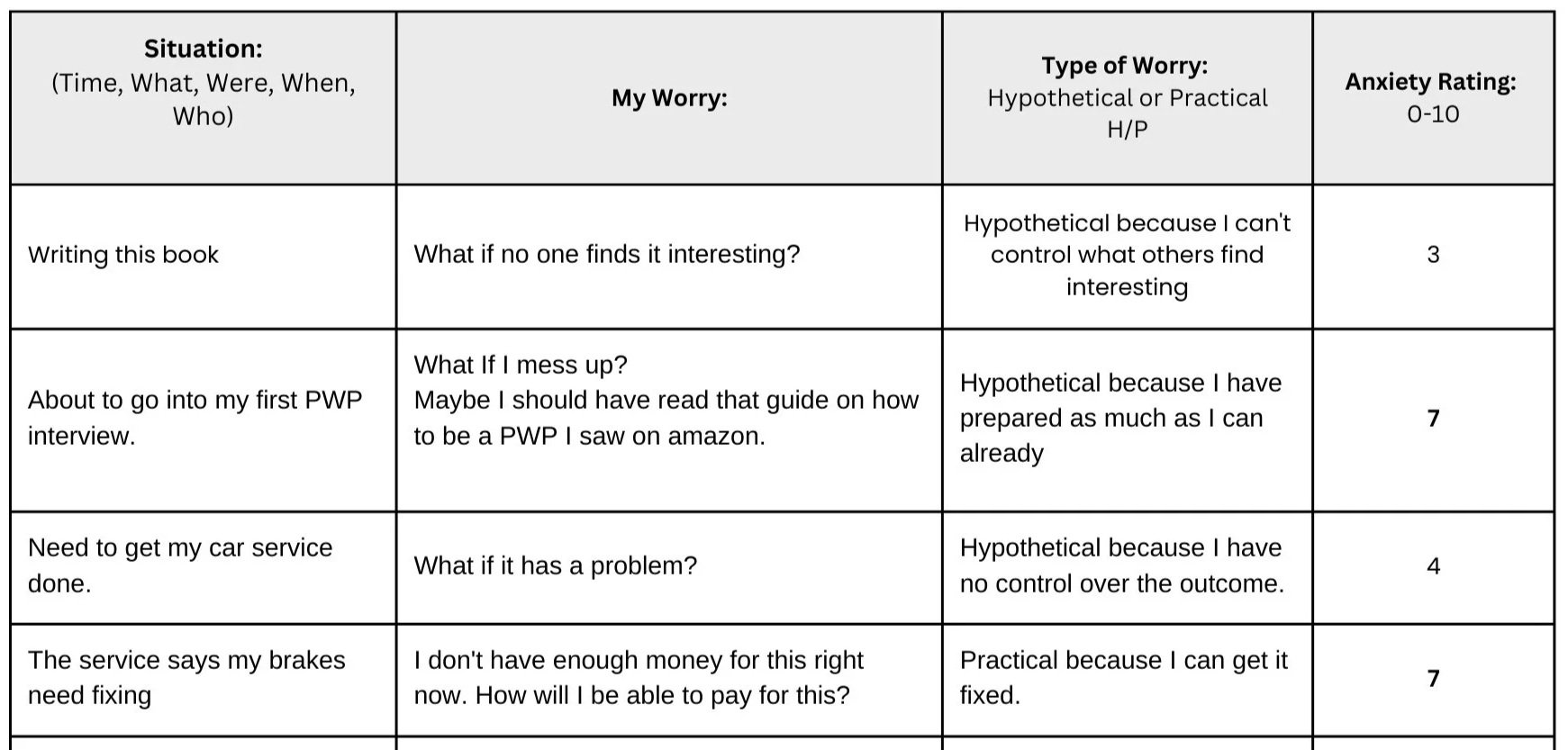

Step 3: Worry awareness training (worry diary).

Patients with GAD can start to worry almost automatically without much conscious effort. They can become so efficient that they may not even be able to recognise or disclose all the small things they are worried about. It's not uncommon for a patient to come into treatment for anxiety but be unable to say what they are worried about (“I just feel anxious”). Patients are better at recognising the big things causing them to worry but have little understanding of their whole worry experience.

Worry Awareness Training is designed to give the patient a better understanding of what their triggers are, what their worries are and gives them the opportunity to classify them as hypothetical or practical.

The way we do this is by the use of a worry diary: see an example below.

A typical worry diary contains:

The date and situation column:

This column is designed to get the patient to realise the link between events and their worries. This can sometimes help them remove or fix certain triggers. E.g. If a patient was always worrying when they first woke up and spent 15 minutes worrying in bed before they got up. A simple fix would be to get them to get up straight away and get on with their day with an activity.

The worry column:

This section needs to be as detailed as possible and should almost mimic what goes through the patient's mind in the moment. Just simply writing “I was worried about work” provides little therapeutic benefit compared to “My boss has already been caught being late a few times. What if I miss my next deadline and get fired”.

Anxiety level:

This can be a useful tool. Often the same worry can span multiple days or weeks and seeing the anxiety level reducing can provide comfort to the patient that the treatment is beneficial even if the same worries keep reappearing. It can also help a patient realise if they are having a lot of small worries which combined are leading to them feeling overwhelmed.

Hypothetical or practical:

The patient should also try to distinguish what type of worry it is. This allows them to act appropriately to the worry, and either select worry time, or problem solving (more on this later).

It can be a good idea to get them to write why they think their worries are either hypothetical or practical to start with. That can help you see if they are doing it correctly.

The second to last worry in the diary is an example of when a worry can seem like both a hypothetical and practical.

Think through this worry based on what you have learnt in this chapter. How would you break down this worry with a patient?

Hypothetical part: “What if I get fired?” is definitely a hypothetical worry as you can not control what your boss decides to do.

Practical part: The patient does need to find a way to get to work or a way to talk to his boss about his lateness.

Click on the worksheet for an editable PDF worry diary:

Step 4: Worry Time.

Worry Time is one of my favourite skills to teach a patient. It is highly effective and works very quickly to reduce a patient's worries. It is not uncommon for patients to be lifelong worriers, then two weeks or so after using this skill to reflect that they don't feel anxious anymore. I have heard many PWPs who do not like worrytime. I feel this comes down to them not understanding the rational or the science behind how it works. Hence why I created the maintenance cycle on this page.

What is Worry Time?

Worry Time, also known as worry postponement, or stimulus control, is a strategy designed to allow the patient to delay and control when and where they worry. The patient will select a 0-20 minute window a day when they are allowed to worry but they will attempt to contain or refocus away from worries for the rest of the day.

The aim of this being to give the patient control back in their life and improve quality of life and functioning. It is not designed to completely eliminate worry (an impossible feat) but in my experience, it goes a long way towards this. Worry Time is only for hypothetical worries. Practical worries should not be postponed.

Why Does it Work?

Step 2 Worry Time does not have as much research base as other CBT techniques and the theoretical underpinnings are not as well understood.

However, based on the maintenance formulation in the start of this chapter, a possible maintenance cycle goes like this:

“Intolerance of Uncertainty -> Worry Behaviours -> Temporary Relief -> Increased Intolerance of Uncertainty.”

This cycle has two points you can break:

1) The worry behaviours:

Worry Time aims to replace a patient’s worry behaviour of excessive worrying, with worry postponement. This causes the patient to realise they didn't need to worry for the few hours until worry time. They effectively stop the constant use of worry behaviours during this time which breaks the cycle.

2) The intolerance of uncertainty:

Worry Time also weakens the intolerance of certainty. When you postpone worry, you learn to tolerate uncertainty better until your worrytime. Once the intolerance of uncertainty is reduced, a patient is less likely to naturally want to engage in their worry behaviours next time, therefore weakening their intolerance of uncertainty further. It is not uncommon to find patients reacting better to uncertainty after worry time without the need to target it directly (which step 3 methods aim to do). This does not necessarily happen consciously (most PWPs never even inform a patient of intolerance of uncertainty), patients sometimes just say they simply were not feeling as worried.

Worry Time Metaphor: Cleaning the Dishes:

Depending on the psychological literacy of the patient you may not be able to convey all of this knowledge about why worry time works. It is not actually needed. Many PWP just teach the steps, and the patients follow on blind faith. However, having a good metaphor can go a long way in explaining this without needing to explain the whole maintenance cycle for patients to find that the strategy seems strange or has reservations about trying it.

Cleaning the dishes metaphor:

Imagine a parent was washing the dishes one day. Their child (aged 4-10) came up to them and asked them to play with him. What would the child do if the parent just ignored them? It would probably ask again and again, maybe it would scream and shout as they feel they are not being heard. Well, that's what a worry does. If you just try to ignore it, it gets louder.

Now imagine the same situation, but instead of ignoring the child, the parent nicely and firmly told the child they would play with them in just a few minutes after they had done the dishes. The child is much more likely to go away for a few minutes until the parent comes to play. This is how worry time works.

However, it relies on you actually doing the worry time. If you ignored your worry and then failed to do worrytime. It's just like a parent who lied to their child. Would they listen to their parents next time they promised to play with them later?

The more you practise Worry Time, the more the worry learns to leave you alone.

Worry Time Steps.

Worry Time has 5 main parts:

Part 1: Schedule when the patient will have worry time:

Aim for 20 minutes as a good starting point. Some people may require longer. If so, aim to reduce this as time goes on.

Aim for the evening: Around 7pm. Not too late as thinking about worries late at night could interfere with sleep.

I wouldn't recommend scheduling Worry Time in the morning, as it leaves the whole day for worries to come up and then people have to wait till the next day.

Patients can set reminders on a phone to remind them. Consistency is key for a new habit.

Part 2: Write down worries throughout the day:

Continue to use the worry awareness (worry diary).

Recognise and classify worries as hypothetical and practical.

Get patients to add to their worry diary as soon as they can.

Part 3: Refocus during the day:

Worry Time only works if the patient actually contains and postpones the worries during the day.

Instruct the patient to not engage in the worry or any worry behaviours.

After they write down their worry, they should refocus and get back on with the day.

Part 4: Worrytime:

There is nothing in particular the patient needs to do during this worry period. They can feel free to worry during this time about anything in their diary.

If their diary has no worries, then no Worry Time is needed. Get the patient to reflect on that.

Remind the patient that Worry Time is only for hypothetical worries.

Ensure the patient does distract themselves during Worry Time. It needs their full focus. Do not multitask.

Set a timer to start so they know when to stop.

Old worry diaries can be discarded after they finish Worry Time. If not, then the patient will have an ever growing list of worries. New day, new diary.

Part 5: Refocus After:

After Worry Time, the patient needs to refocus away from the worries again and get back on with the day.

If a worry occurs after their Worry Time then they can write it in their worry diary for tomorrow.

Start a new worry diary for the next day.

Step 5: Refocusing skills.

Refocusing is an important element of worry management. Worry Time only works if the patient does not continue to focus or act on the worries outside of worry time.

Does that mean the patient should try to push the worry out of their mind at all costs? The answer is actually a no. Let's explain why with a pink elephant.

Try this experiment on yourself.

Pink Elephant Experiment: I often do a quick version of this with patients when discussing refocusing.

Ask the patient how many times in the last year they have thought about a pink elephant. The answer is usually zero times (Strangely, I have had a couple of patients who have said they had).

Then ask them to try out an experiment for 15-30 seconds.

Ask them to:

Count how many times they think about a pink elephant.

Try not to think about a pink elephant.

Outcome:

Most patients end up thinking about a pink elephant. This is because when we try to push something out of our mind it doesn't work. If the patient did manage to not think about a pink elephant, they might be good at refocusing already and worth exploring what they were thinking/doing during the experiment.

How to refocus?:

Anxiety aims to take our focus away from the here and now and onto our worries. Refocusing using our senses or reengaging back on our day can bring us back to the moment.

Here are a few ways to refocus:

Refocusing with Tasks:

Patients can refocus using tasks or activities. Distraction tends to be bad if used as avoidance. However, refocusing back on the tasks at hand which you were doing before the worry occurred can be useful. E.g. If you worried at work, try to get back on with your work. It is a powerful combination with Worry Time because you are not ignoring the worry, you are delaying it until later.

Sight:

The patient can focus on what they can see. They can make this into a small game. Get them to look for all the white objects in the room beginning with the letter “B” for example.

Touch:

The patient can focus on what they can feel. Can they feel the chair they are on? Is it a hard or a comfy chair? Can they feel their clothes on their skin or the floor they are standing on?

Hearing:

What can they hear? Get them to focus on sounds inside or outside of their house.

Smell:

This one relates to aroma, which has been shown to be highly linked to memory centres. These can help you get your mind away from the worry and in some cases help you think about something else. Consider scented candles or get them to focus on smells in the environment they are in.

Taste:

Taste can be a good refocusing activity. Get the patient to try mindful eating: highly focusing on eating something while really searching for all the flavours and textures. Although be aware to not encourage the use of eating in reaction to anxiety as this can become a negative link.

Full PWP textbook available on Amazon

〰️

Full PWP textbook available on Amazon 〰️

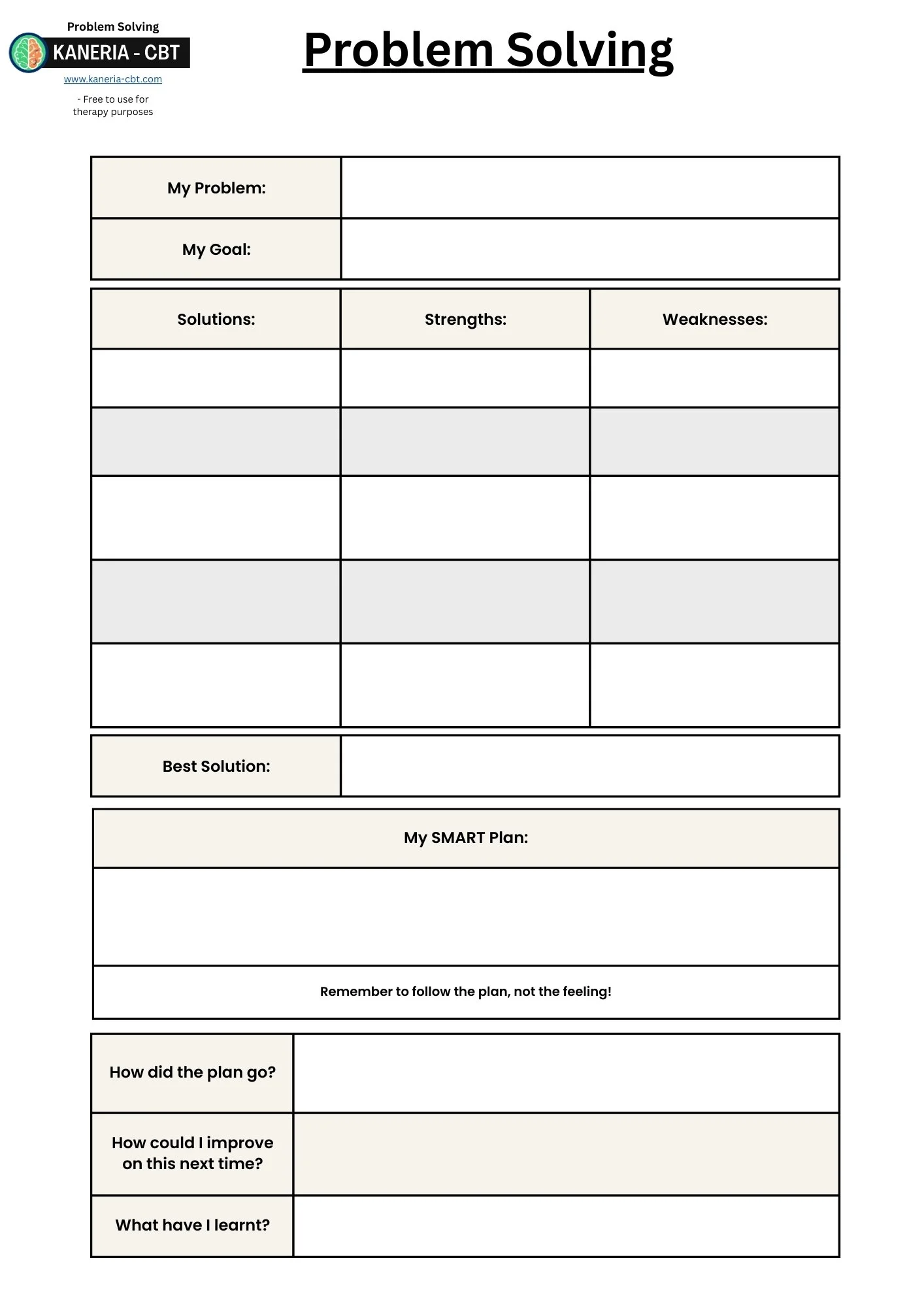

Step 6: Problem solving.

When a patient has a lot of practical worries the intervention used is called problem solving. Problem solving can also be used for depressed patients if their depression is maintained by life problems. However, when treating GAD, problem solving can be taught before or after Worry Time based on patient choice.

When an anxious patient engages in avoidance of fixing their problems, their repertoire of problem-solving skills is often reduced in favour of always avoiding problems. This avoidance often interrupts the patient's ability to effectively solve life's problems. When problems remain unsolved, their impact increases, further causing more anxiety. This avoidance also causes patients to see any potential problems as more catastrophic issues or feel they can not cope. Increasing their anxiety further. Patients may often reflect that problems feel too hard to solve or that they can not cope or handle problems. This is where problem-solving skills can be helpful to incorporate into therapy. However, it is important to remember that problem-solving isn’t about solving the patient's problem. It's about teaching the patient the process of doing so, so they can keep doing it themselves. This way the skills transfer to after therapy ends. Problem-solving can be its own therapy intervention on its own (D’Zurilla and Nezu, 1999) but has been added into step 2 worry management.

Effective problem solving typically follows 8 simple steps:

Step 1 - Problem Identification.

Step 2 - Goal setting.

Step 3 - Identifying possible solutions.

Step 4 - Evaluating each solution.

Step 5 - Selecting an ideal solution.

Step 6 - Planning for implementation.

Step 7 - Carrying out the plan.

Step 8 - Reflecting or refining.

Steps in problem solving.

Step 1 - Problem identification:

The first step is to identify the problem. “A problem well defined is half solved”. At first, this sounds obvious, but it is very easy for anxious patients to place the wrong focus on their problems. For example, if a patient's boss has given them too much work, a patient might consider their boss to be the problem. This can lead to ineffective problem solving as the solution becomes to fix their boss. Alternatively, if the problem was identified as “I have more work than I can manage right now” then the solution is to lighten their workload, which is more achievable. This step is started by the use of the worry diary but ensuring the patients select the right focus is often needed for the rest of the process to be effective.

Step 2 - Goal setting:

Once the patient has identified the correct focus of the problem, then it needs to be converted into a goal which can be solved. This places the patient from a problem focused mindset into a solution focused mode. Going back to the last example, the goal could be to “find a way to achieve my work or lighten the load”.

If the patient struggles it can be worth prompting with:

Asking more details about the problem as it currently stands.

Focus on what can be fixed or improved.

Asking what they want the situation to be.

By giving the patient a “magic wand” to fix their problem and see what would be different.

Asking what someone else might want to change if they were in a similar situation.

Some tips for setting a well-defined goal are to:

Get the patient to realise the difference between facts or what they assume is occurring. If the patient has misinterpreted the problem due to any cognitive distortions the goals/problems may not match up with reality.

Make sure the goal is well-defined without any vague language.

Ensure the goal is realistic. If the situation is outside of control or is extremely hard to solve then the goal can be either to improve the situation slightly or focused on “how to cope” better through the situation.

Ask what the obstacles in the way of this ideal situation are. Then fixing these obstacles can be set as the goal.

SMART goals can also be used here.

Step 3 - Identifying possible solutions:

The next step is to consider as many possible solutions to the problem as possible. The key thing here is the therapist needs to take a backseat and let the patient learn to consider their own solutions. No solution is a bad solution at this point, so refrain from any judgement. Encourage the patient to put down silly, bad or even non-legal solutions. The idea is not to do those bad ideas, but they can help you think of more ideas and improve creative solutions. It is also recommended that patients put down “do nothing” or “put it off too later” as a solution. These help the patient avoid these often unhelpful solutions in the next step.

It is advised to consider these things when identifying solutions:

Strategies: Some ideas patients come up with can be called “strategies”. These refer to more vague ideas or concepts. For example, a possible strategy could be to “talk to my boss”, or “clean the house”, or “borrow money”. These are general strategies, themes or concepts, as the exact content of the solution has not been decided on yet.

Tactics: The patient also needs to consider actual “tactics” within these strategies. Knowing you want to talk to your boss about your workload is only half the battle, you also need to consider how, where, when and what you are going to do. This helps make the solutions more defined which aids the next step.

Role Models: If the patient struggles to think of solutions, it can be worth prompting them on how their role model, friends or family would try to tackle their problem.

Combine good ideas: Patients may come up with solutions that pair together well. These can be combined into a single solution, or a series of steps.

Step 4 - Evaluate each solution:

Step 4 is where the patient looks at their list of solutions and considers the strengths and weaknesses of each one. This will help them find the best solution. This should eliminate the silly, bad and non-legal ones (Hopefully!... But I do live in fear that one day I will find out that a patient of mine has robbed a bank after doing problem solving). Usually “do nothing” or “put it off too later” seems like a bad idea at this stage as well.

Patients should be prompted to consider:

The likelihood of success.

Their motivation for each solution. Even if they have the best solution in the world, but they would never follow through, then it is not a good solution.

How realistic the solution is. A good solution on paper that would never work in practice due to the patient's situation or lack of resources is not a good solution.

Patients can consider the difference between the short-term and long-term effects of the solution. Often good solutions can be harder in the short-term but lead to better long-term options. Alternatively, some bad solutions may seem good short term and cause many long-term problems.

Facts vs opinions: The patient needs to consider the facts regarding the strengths and weaknesses. Sometimes it could just be a fear or a worry. E.g. "There is no point asking my friend for help as it will only annoy them". In reality they might be more than happy to help.

Step 5 - Select an ideal solution:

The patient should now have a good idea of what the best solution is. This may be vastly different than what you as a therapist would have chosen but remember, problem-solving is about the patient and them picking their ideal solution.

Common issues patients may have:

"No solution seems to be best": Problem-solving is not about finding the perfect solution; it is about not getting stuck or avoiding trying to fix problems. Get the patient to try to pick the best solution they have come up with at this time. They can always come back to the list and try again if the solution isn't successful. We often learn from failures just as much, if not more than successes.

Only focusing on the short term: Sometimes patients may pick a bad solution which only works in the short term. Get them to consider the short-term vs long-term solutions. But remember, it is still their choice of what solution they consider the best.

"No good solutions": If the patient does not like any of their solutions, then they can go back to the solutions stage and think of some more. They can also get a friend or loved one to help them consider any solutions they may not have considered. Sometimes an outsider can offer good solutions, as they are less close to the problem. Also getting patients to recognise not all problems have ideal solutions e.g. “having to tell someone bad news”. But they can still try out the best solution they have available under the circumstances. If the issue is outside of their control, they may not be able to completely "solve" the problem. Focus on the parts within their control or focus on what they can do to improve or cope despite their problem.

"Fear of picking the wrong solution": Problems can be scary. We can never truly know the outcome of our actions. Prompt the patient to try and if it doesn't work then they can always try problem solving again. Often doing something is better than doing nothing.

"Can not choose": If a patient states they can not choose, then remind them that choosing to do nothing is still making a choice. That's why I recommend adding "do nothing" and "procrastinate" to their solutions list. Patients always have to pick at least one option. If they decide to do nothing, at least they are aware of its strengths and weaknesses.

Step 6 - Plan for implementation:

Now the patient has selected their solution. It is time to put it into action. For some solutions, this will be easy and just requires some commitment. There is often a gap between planning and action. So, the patient needs to consider actually how they are going to implement the solution. They can consider scheduling, the 4 W’s (what, when, where and who) or using SMART goals to develop a plan. Not all plans need to fit every category, but usually the “SMARTer” the better.

SMART is an acronym which stands for:

Specific: A plan needs to be focused and not vague. This helps patients identify exactly what they want to achieve. Consider using the four W's: "what, when, where, and with whom".

Measurable: The patient should have a good idea about how to measure that the plan is working. That way the both of you know if it is working or if the solution needs changing.

Achievable: The plan should be reasonable and achievable. If the solution is not achievable, it isn't likely to resolve the problem. If a solution is too big, break it down into smaller goals.

Relevant: You need to make sure the goal is relevant to your problem.

Time-Bound: Your goal needs to have a target date or time to be completed. Adding a timeframe to the plan can prompt the patient to be more likely to achieve follow-through.

Step 7 - Carry out the plan:

The next step is for the patient to go away and do the activities they have planned.

Reinforce the idea of “follow the plan not the feeling”. Following through is entirely up to your patient to complete.

Step 8 - Reflect or refine:

After attempting the solution, get the patient to review how it went.

If it solved the problem: Great!

Get the patient to reflect on why it worked and what they can learn for future problems.

Ask them if this has changed how they view problems, the act of avoidance of problems or how they will deal with problems going forward.

If it did not solve the problem: Not so great, get them to reflect on why…

Ask the patient what went wrong?

Was it a bad solution?

Did a barrier get in the way?

What can they do differently next time?

Go back and think of another solution.

Retry the plan and overcome the barriers.

Written by David Kaneria

CBT Therapist & Previous Psychological Wellbeing Practitioner (PWP)

Author of Low-Intensity Cognitive Behaviour Therapy; A Psychological Wellbeing Practitioner (PWP) Handbook

Low-Intensity Textbook:

For more information on Worry Management and much more, check out my PWP textbook on amazon.

Anxiety self help book for patients:

If any patients could benefit from any further support after therapy to maintain their progress my self-help book contains all the step 2 depression strategies in one easy to understand book.