Welcome to the PWP Corner’s section on Behavioural Activation.

The PWP Corner is designed for therapists. If you are not a therapist try looking at my self help section instead.

This section has two parts:

2) Information on how to guide a patient through Behavioural Activation.

Behavioural Activation Worksheets:

These are free to use worksheets you can use with your patients.

Click the image to download the worksheet.

ABC Cycle:

Types of Activities:

Five Areas:

Depression Cycle:

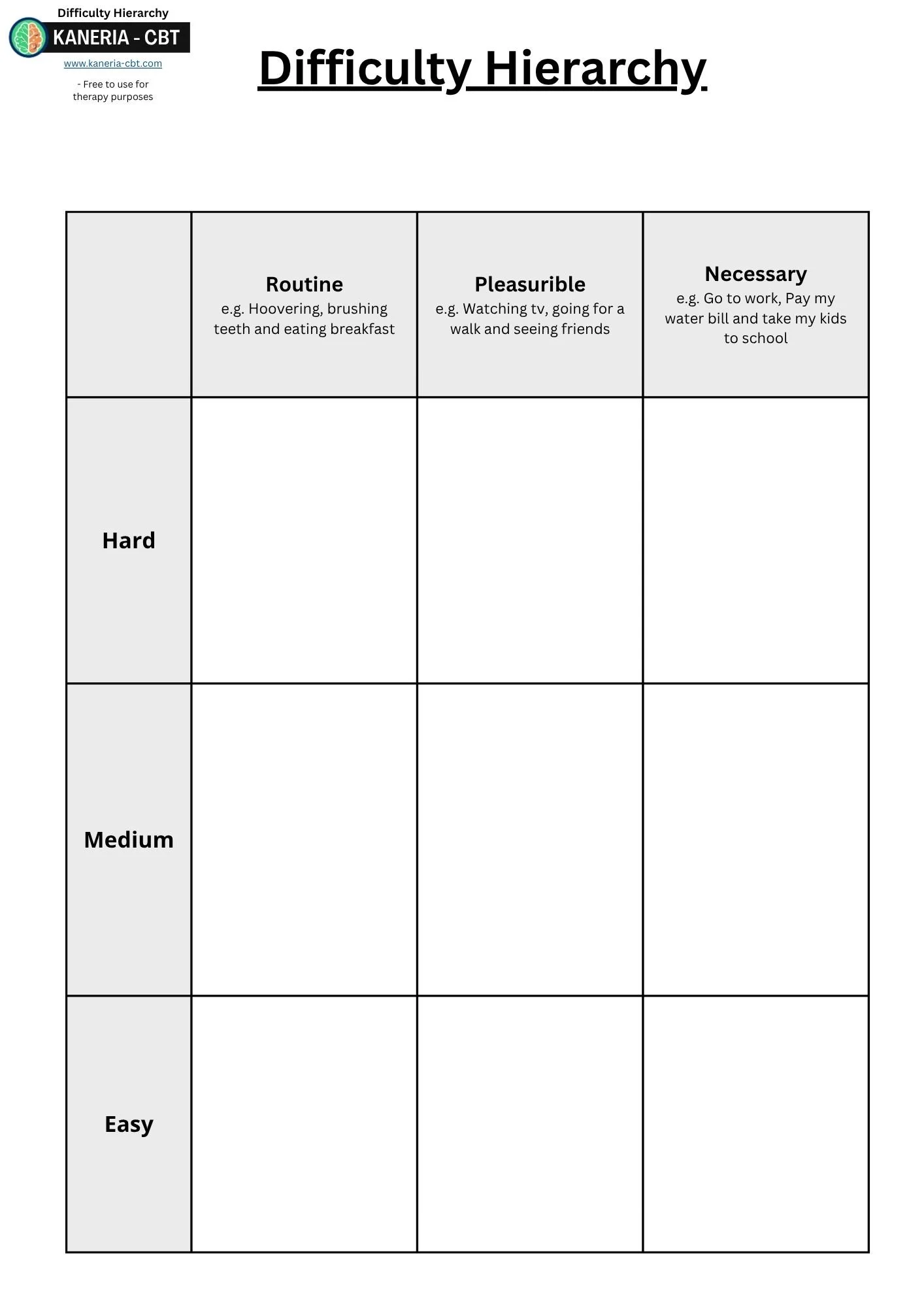

Difficulty Hierarchy:

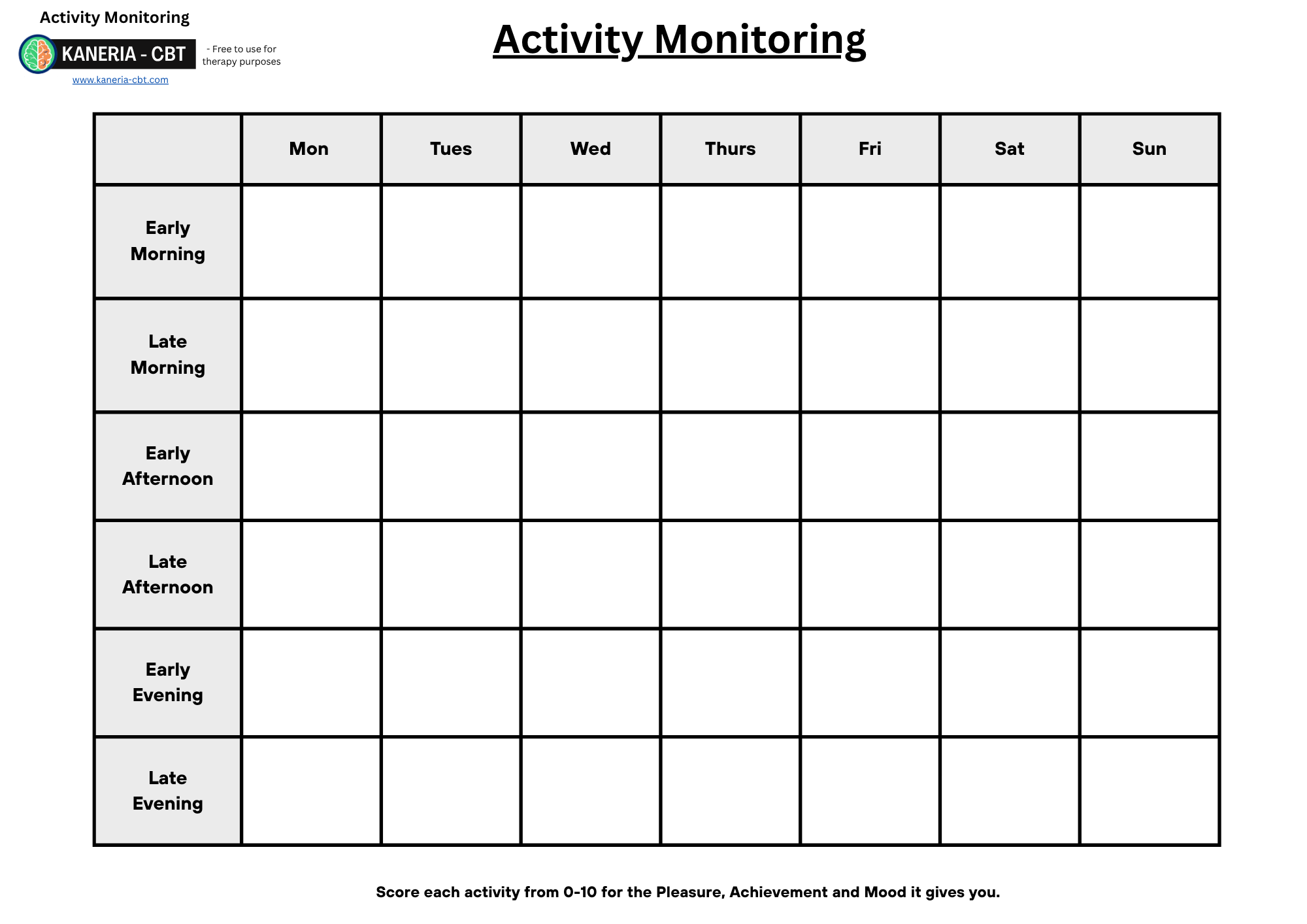

Activity Monitoring:

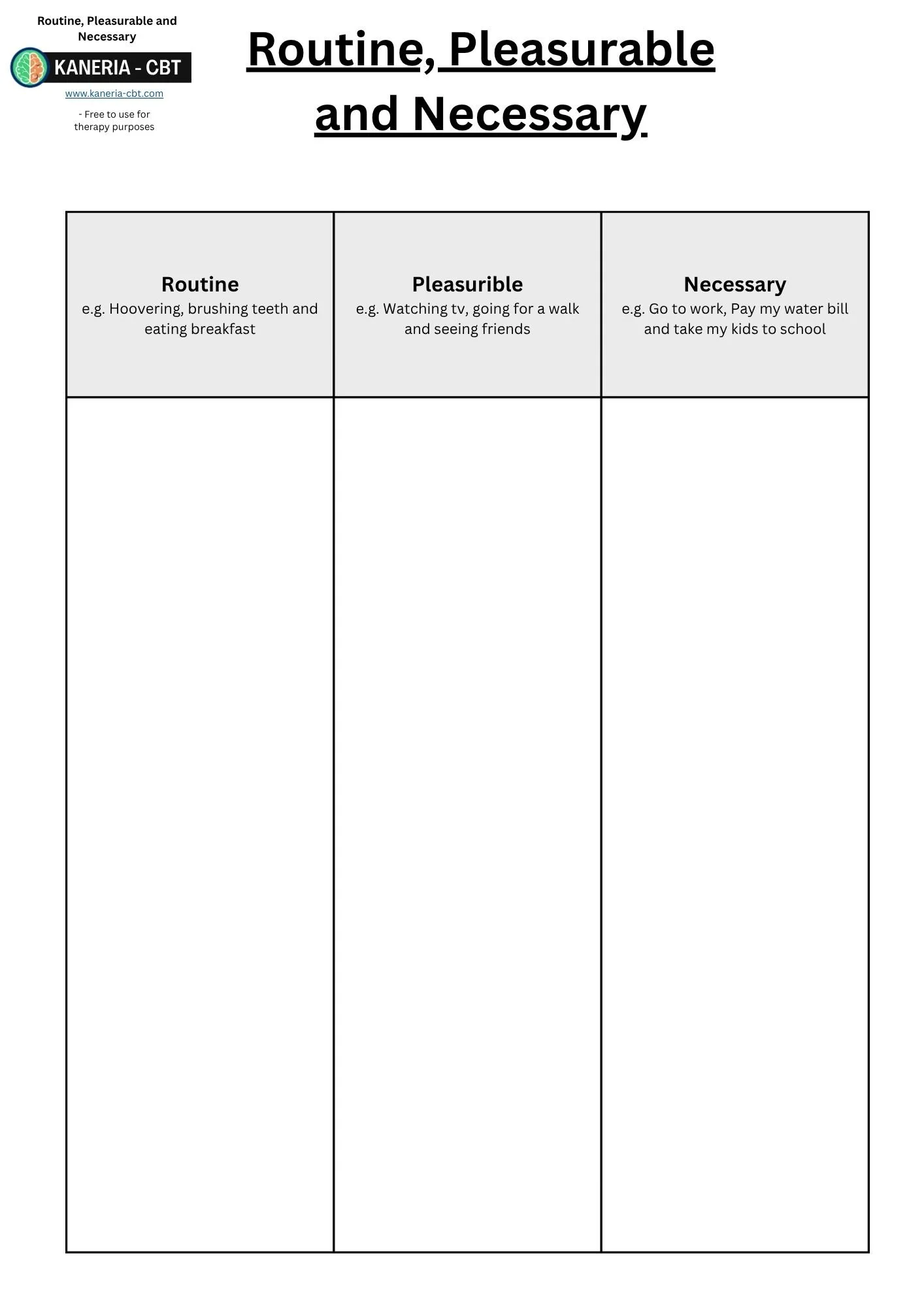

Activity List:

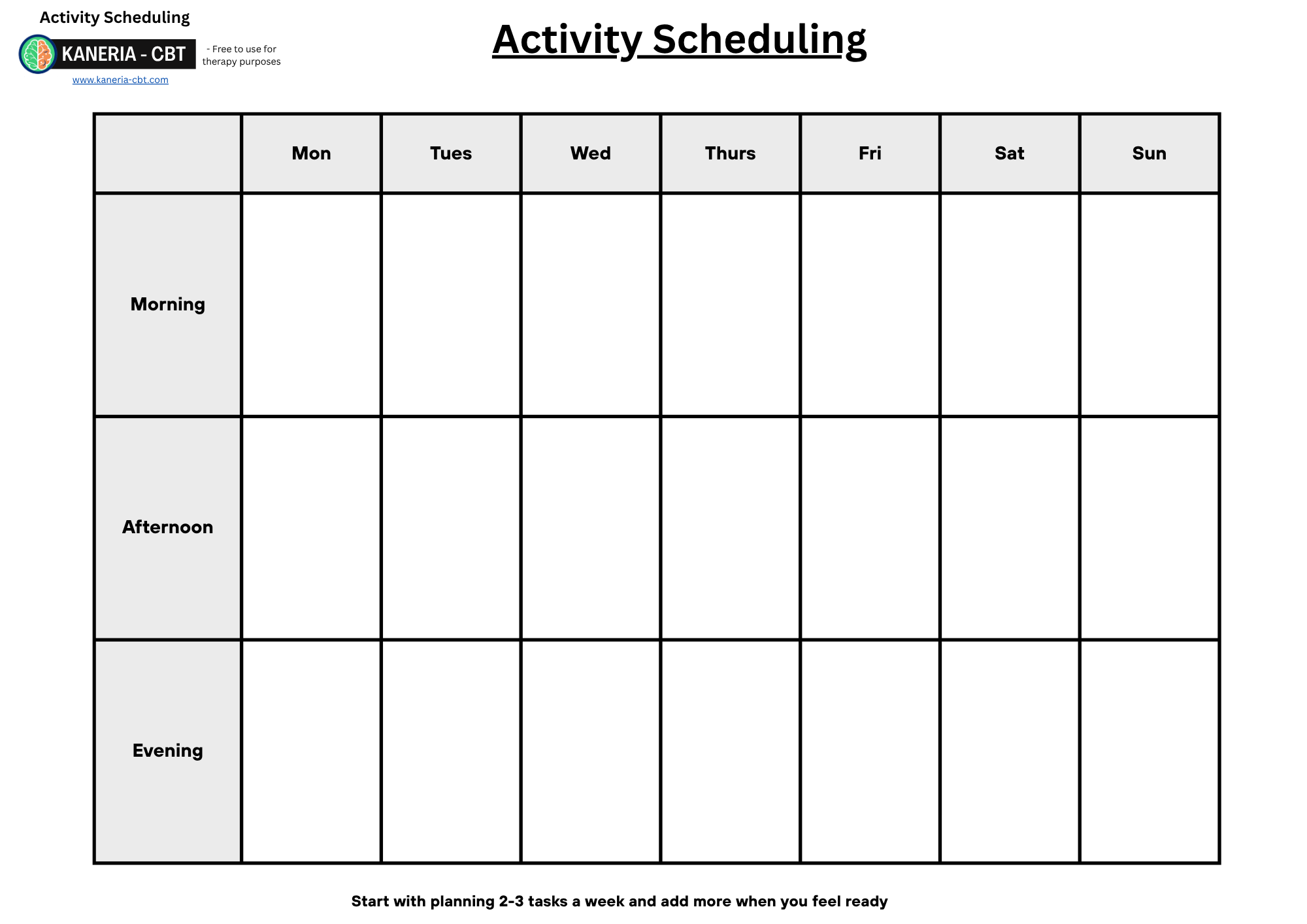

Activity Scheduling:

Behavioural Activation Guide:

Behavioural Activation (Martell, Dimidjian and Herman-Dunn, 2010) is a very simple but highly effective strategy based on a behavioural view of depression and aims to improve the patient's activity levels and reduce avoidance. Behavioural Activation has had multiple clinical trials (Jacobson, Martell and Dimidjian, 2001) and systematic reviews have demonstrated that BA is as effective as CBT (Dimidjian et al., 2006; Dobson et al., 2008).

A guided self-help version of BA has been developed (known as Low-intensity BA) and has been shown as an effective treatment for use within NHS Talking therapies (Richards et al., 2007). It consists of psychoeducation and a structured way of introducing and scheduling in activities to overcome the lack of motivation present in depression.

The main rationale for what maintains depression when using Behavioural Activation is that:

Low mood causes us to feel less motivated. When this happens, we do a lot of unhelpful behaviours such as putting things off and doing less (Ferster, 1973). This in turn creates less motivation and lower mood. This cycle reinforces itself and can be difficult for patients to naturally escape from.

Therefore, a way to break out of this cycle is to overcome the unhelpful behaviour of doing less / avoidance. This is achieved by forward planning in activities. Once the patient starts doing more, motivation and mood typically rise, which self-reinforces itself.

The Main Steps of BA consist of:

Step 2: Baseline Activity Monitoring (optional).

Step 3: Create a list of routine, pleasurable and necessary activities.

Step 4: Create a hierarchy (rank how difficult these activities are).

Step 5: Activity scheduling (plan in when these activities will take place).

Step 1: Psychoeducation:

Psychoeducation should consist of:

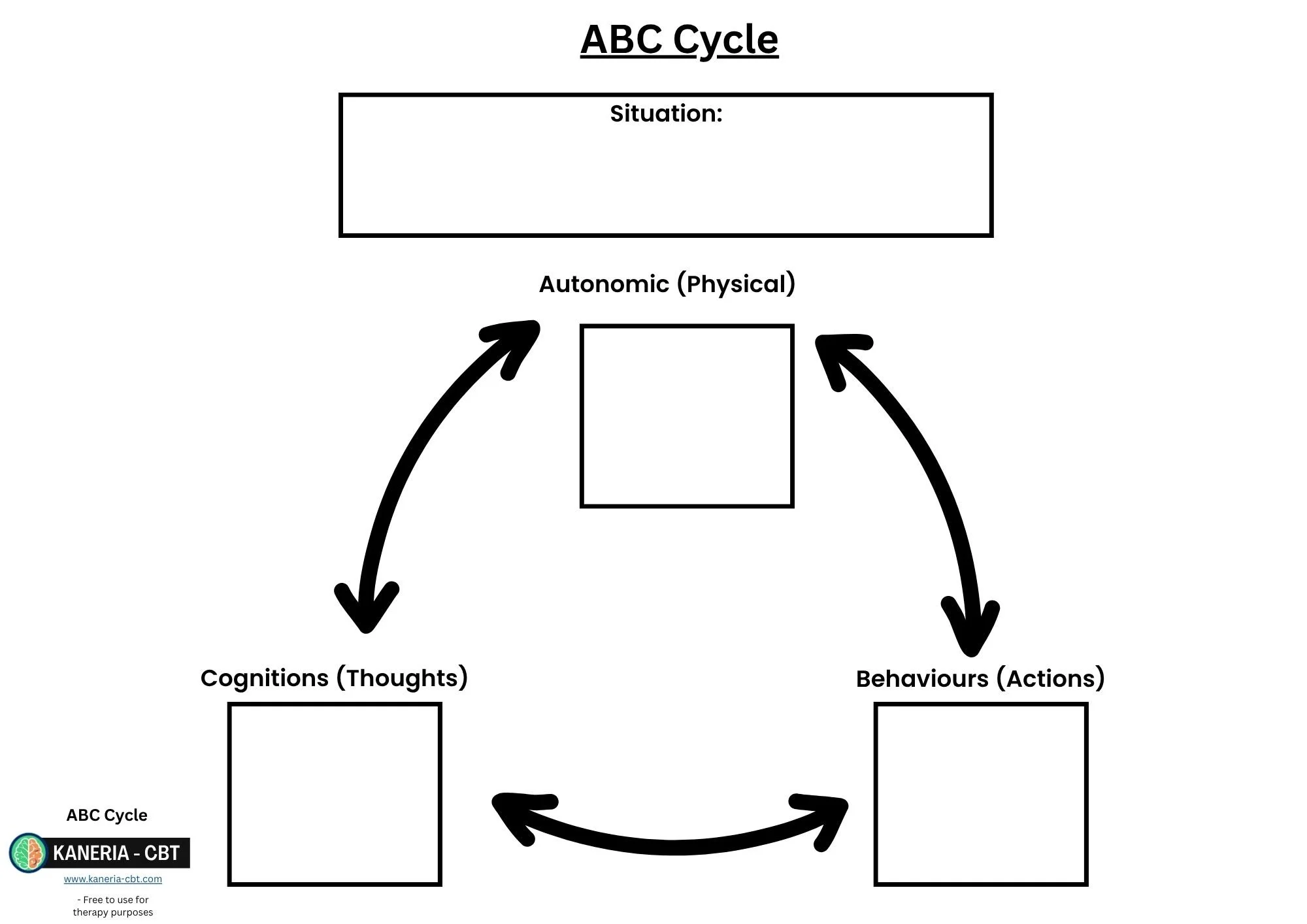

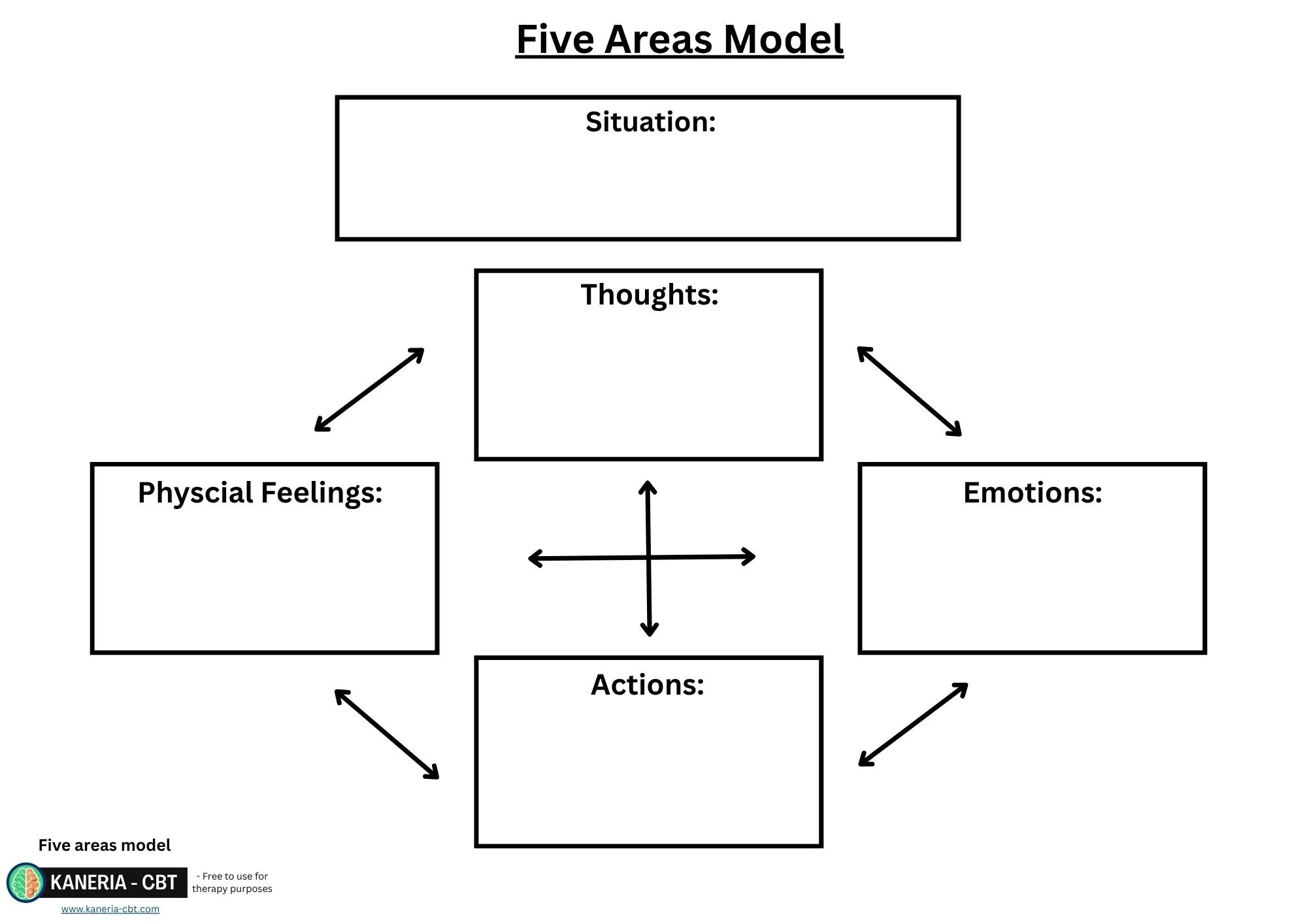

Providing information on the ABC cycle or five areas model and getting the patient to fit themselves into their own cycle.

Exploring the maintenance formulation of depression to help the patient see how a lack of motivation can maintain low mood. Always check if the maintained formulation feels relevant to them.

This can then lead onto a discussion of the downsides of waiting to feel motivated before starting an activity. Then discuss how motivation can be improved and created through the action of starting the activity.

This then leads onto an outline of how behavioural activation works.

ABC Cycle or five areas model:

Always start with an ABC cycle or five areas model as usual. These cycles for depression often involves the patient experiencing low motivation which leads to and a lack of activities and an increase in guilt or self-criticism for being inactive.

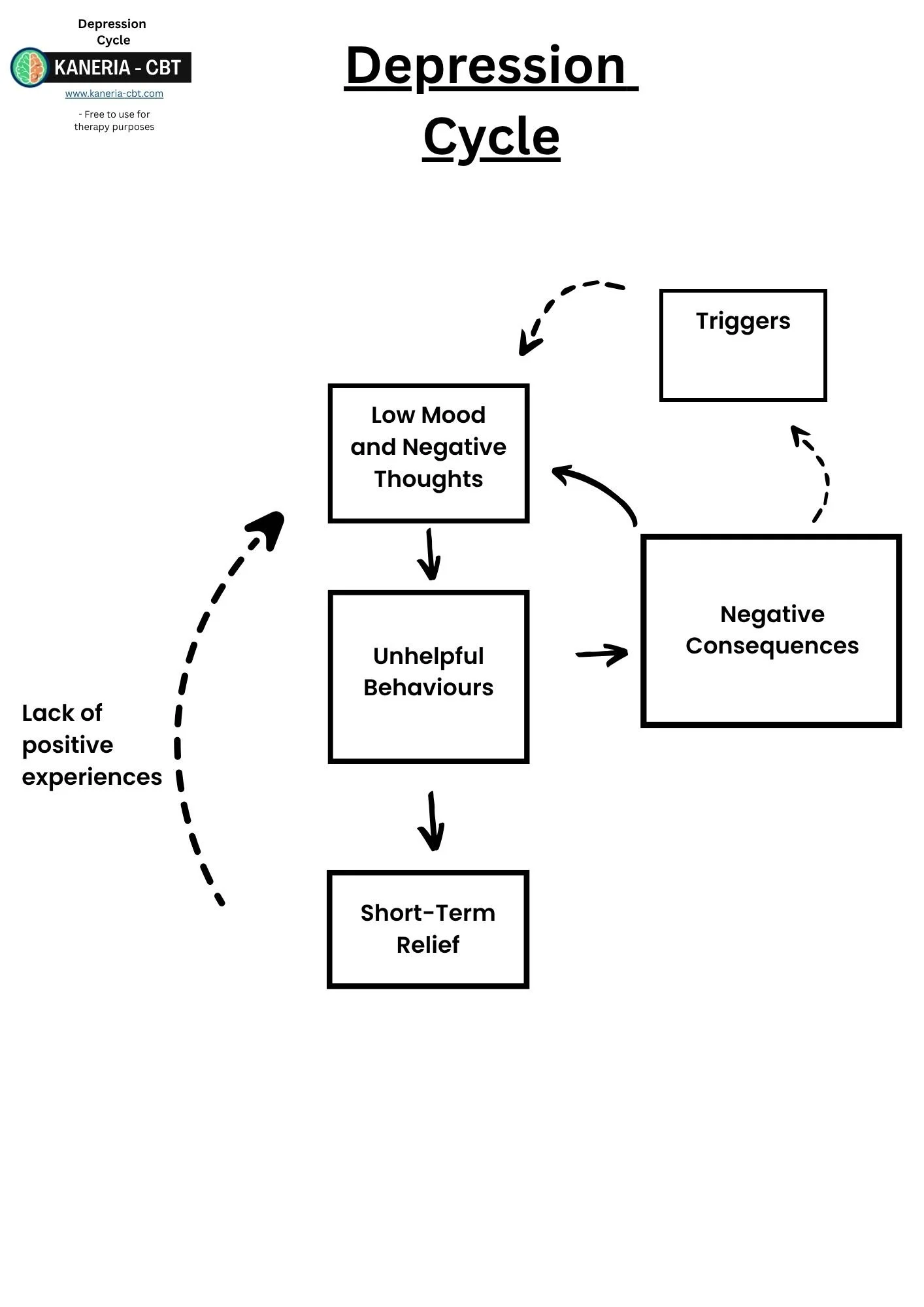

Depression Maintenance Cycle:

It is optional but showing patients a maintenance cycle for depression can be helpful at helping them understand the rationale behind what maintains Depression and why treatment works.

There are many versions of this but they all show similar principles.

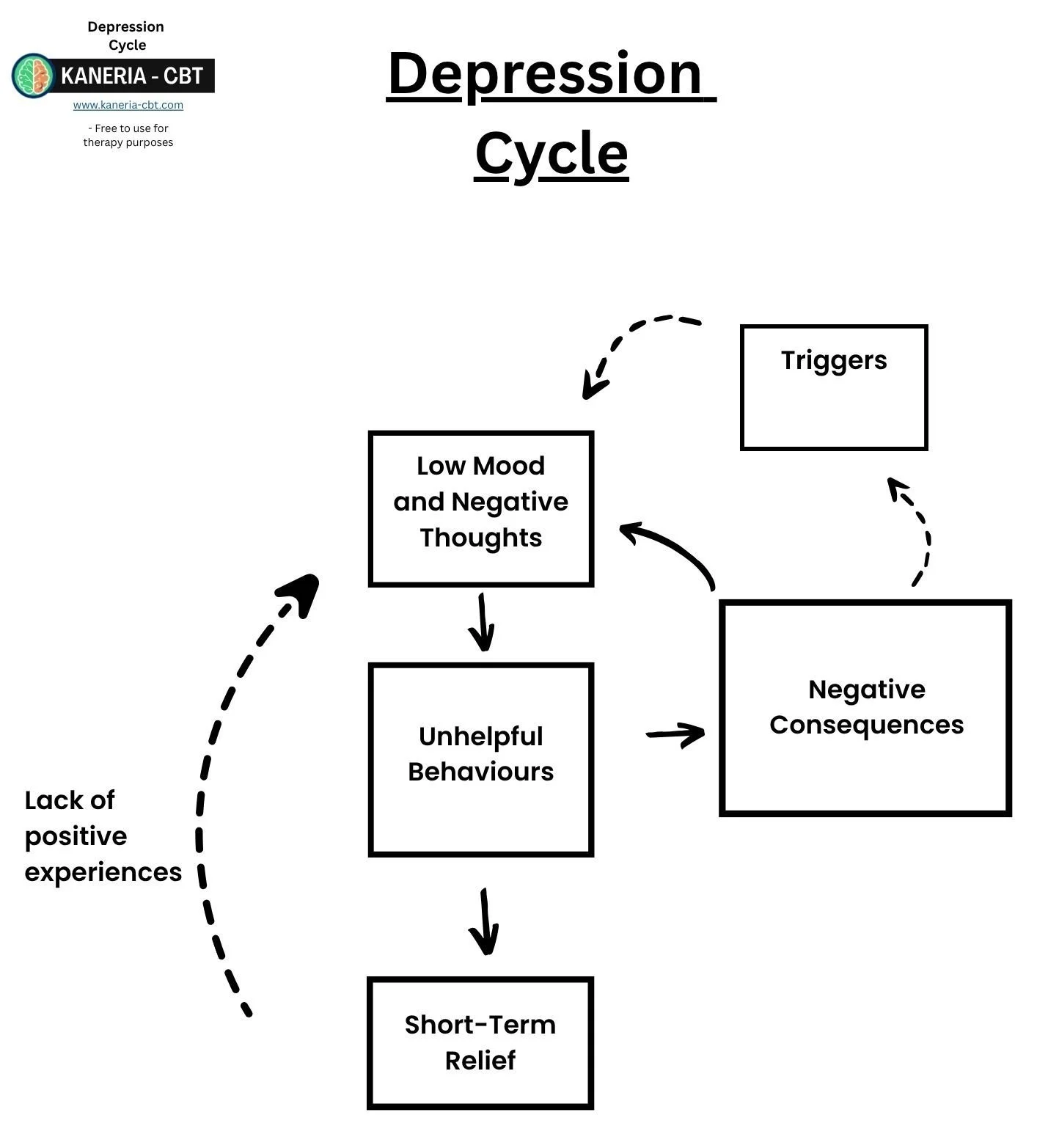

Triggers: Low mood can often be triggered by certain day-to-day situations.

Low Mood: These triggers cause your mood to dip causing our thoughts to become negative and often causing a lack of motivation.

Unhelpful Behaviours: When we are low, we often start to act differently. This can lead to unhelpful behaviours such as avoiding socialising, putting off tasks and doing less.

Short-Term Relief: When low, these tasks feel hard, therefore we get a sense of temporary relief from not having to do the activity. However, this is often quickly followed by guilt, feeling lower or self-criticism for not doing the task. This lowers mood and starts the cycle again. Furthermore, avoiding activities also stops us from having positive experiences which would help counteract the low mood.

Negative Consequences: Often these activities pile up and cause an impact on our life. We can put off responsibilities or stop engaging in meaningful activities. This can make our low mood worse, which starts the cycle again.

Step 2: Baseline Activity Monitoring (optional):

Some PWPs use baseline activity monitoring as the first step of treatment. The aim of this is to find out a bit more about what the patient is already achieving in terms of activity, and it can sometimes help see if the patient is doing too much or has an imbalance of activities in their life (see step 3).

There are various schools of thought on the pros and cons of doing this. Some PWPs omit this step due to time constraints within sessions and the limited number of sessions offered for guided self-help. Assuming a good initial assessment was done and good psychoeducation around the ABC cycle before BA began, then you should have a good idea about the patient's baseline activity anyway.

Step 3: Create a list of routine, pleasurable and necessary activities:

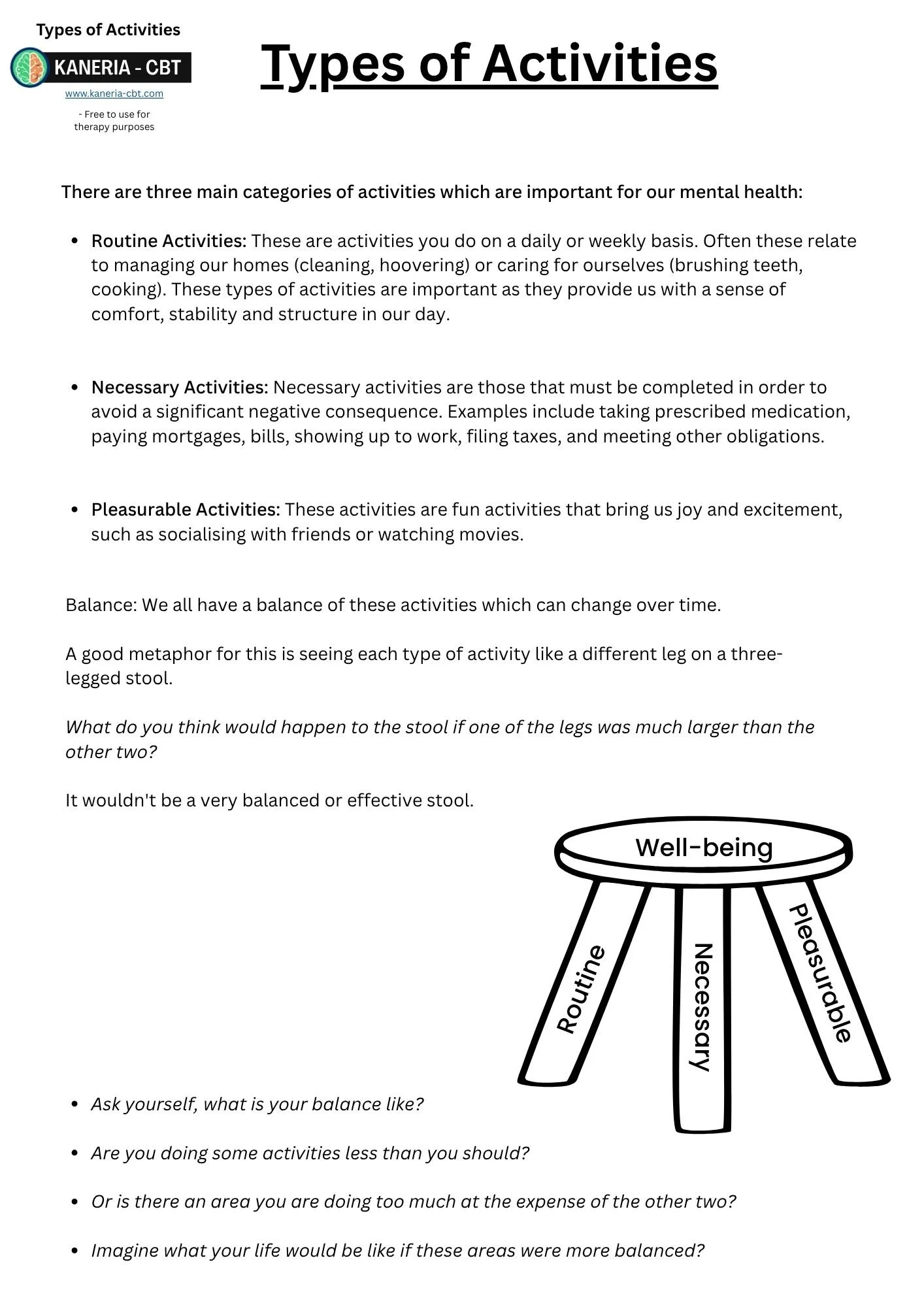

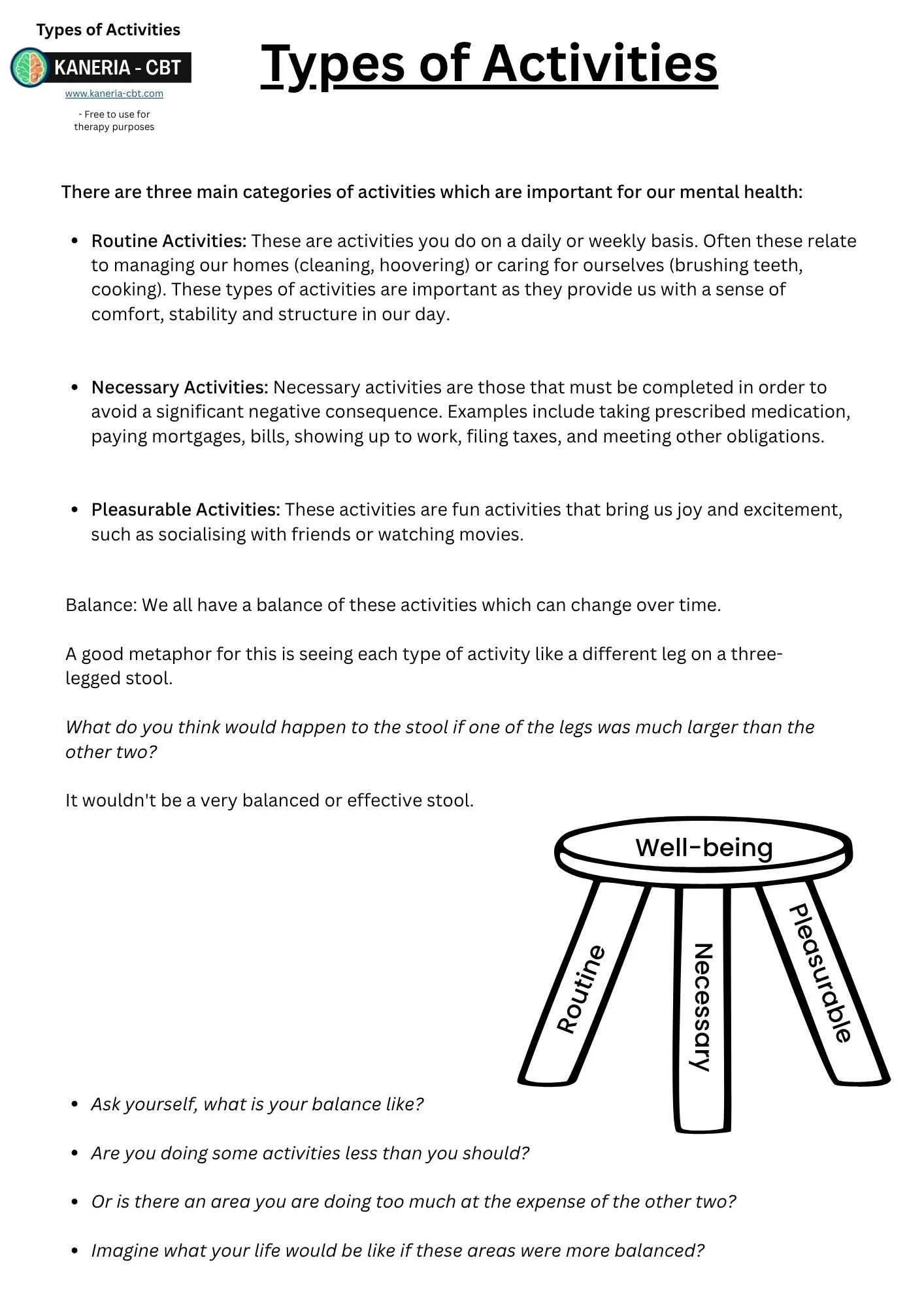

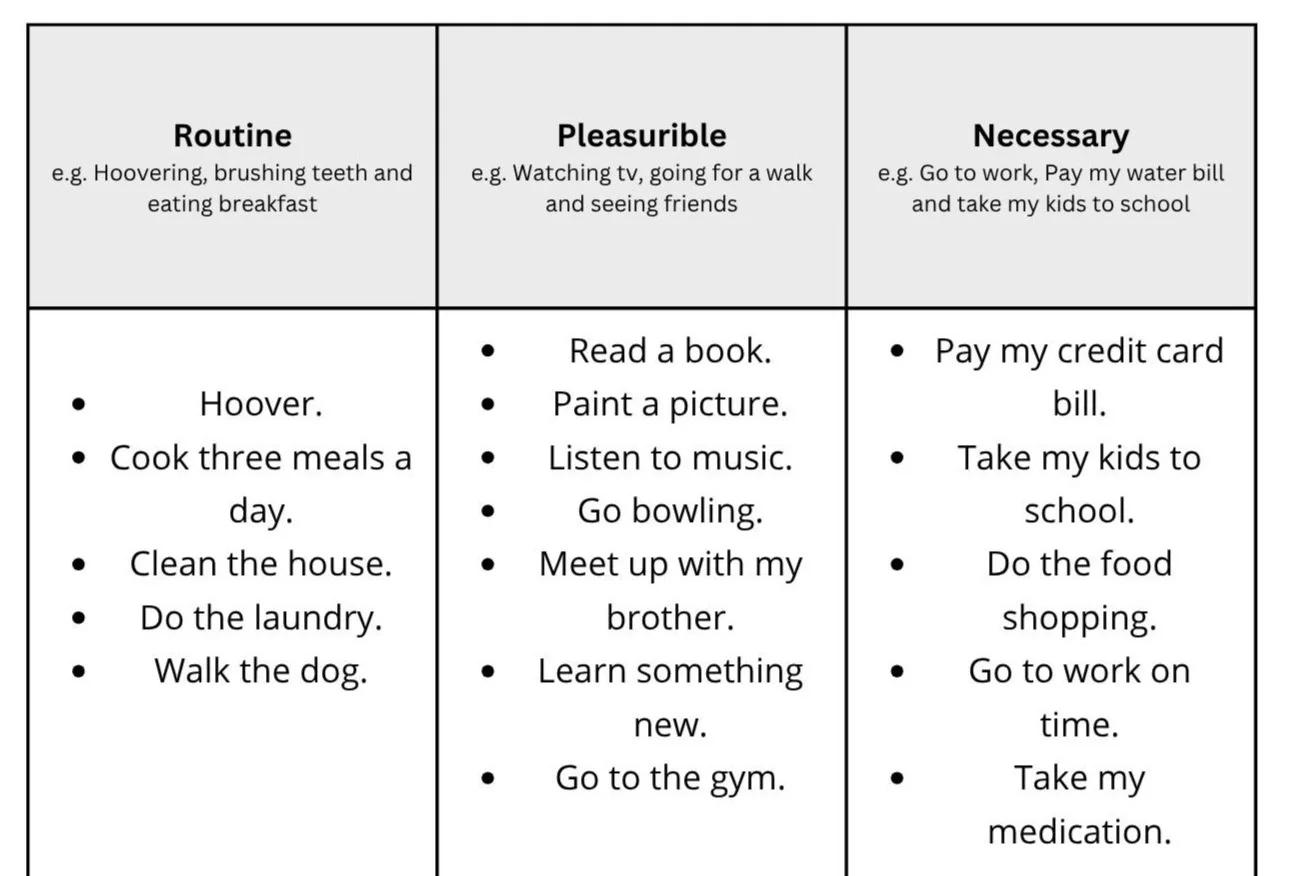

In this step, patients are taught that there are three main types of activities:

The Routine:

This refers to activities that the patient used to do regularly to maintain a regular lifestyle. Often this can be in the form of cooking, cleaning, personal hygiene, exercise or shopping. Life routines are important to give people a sense of comfort, safety and stability in their daily life. Regular mealtimes or sleep hygiene can also be discussed here as these can help regulate the body to the time of day and can improve wellbeing.

The Pleasurable:

These activities are the things the patient used to enjoy before they became depressed. These activities are fun activities that bring them joy and excitement, such as socialising with friends or watching movies. You can also consider things the patient would like to start doing or always wanted to try. These types of activities are helpful in BA as they are naturally self-reinforcing. A patient will enjoy them and want to do them again.

The Necessary:

Necessary activities are those that must be completed in order to avoid a significant negative consequence. Examples include taking prescribed medication, paying mortgages, bills, showing up to work, filing taxes, and meeting other obligations. These are important to identify and work on as failing to do so can cause life problems which worsen depression.

Three legged stool metaphor: Get the patient to think of these three types of activities as the legs on a stool. Ask them what they think would happen if one of the legs is smaller than the other. It would fall over or not be very stable. The same applies when having an imbalance of activities in life. Imagine the stereotype of a person who spends all day on his PC gaming and watching TV. Although they are doing pleasurable activities, they are missing out on doing their routine and necessary activities and may feel depressed. Alternatively, imagine a single parent who has three young kids and is working full time. They may be managing with all the routine and necessary items but never have any time for themself. They are also at risk for depression. The idea is to get a balance between the three activity types. Then ask the patient if they think any of their “stool legs” (types of activities) in their life are out of balance.

Once the patient has an understanding of these three types of activities, their first homework task can be to brainstorm and fill out a list of activities for these categories.

Here is an example of what this could look like once the patient has made a list:

Step 4: Create a hierarchy (rank how difficult these activities are):

The next step is to rank each task by how difficult each activity is to achieve. Easy, medium or difficult. The reason for this is that patients need to start on what they find easy. It is important to remind the patient this is on how hard they will personally find the task to achieve given their motivation rather than how the general population would find it.

Breaking down tasks:

Another important discussion to have with the patient at this stage is on how to break down tasks into smaller and more manageable chunks. This is to make difficult activities much easier to achieve. A common example of this I see in practice is when a patient has put on their list they need to “clean the house”. I don't know about you personally, but even on a good day I would struggle to clean my whole house. It sounds obvious to break things down and to only clean one section at a time. But when a patient is depressed, their problem solving skills can be diminished (see the section on problem solving); and patients can often attempt to over achieve when planning in and underachieve in practice. Having “clean the cupboards in the bedroom” on their list rather than “clean the house” can make all the difference in a patient following through or looking at a large task and becoming demoralised.

The patient should ideally have a good mixture of routine, pleasurable and necessary in each difficulty category.

The task of breaking down activities can be set as a homework task.

Here is an example of a hierarchy using the previous list:

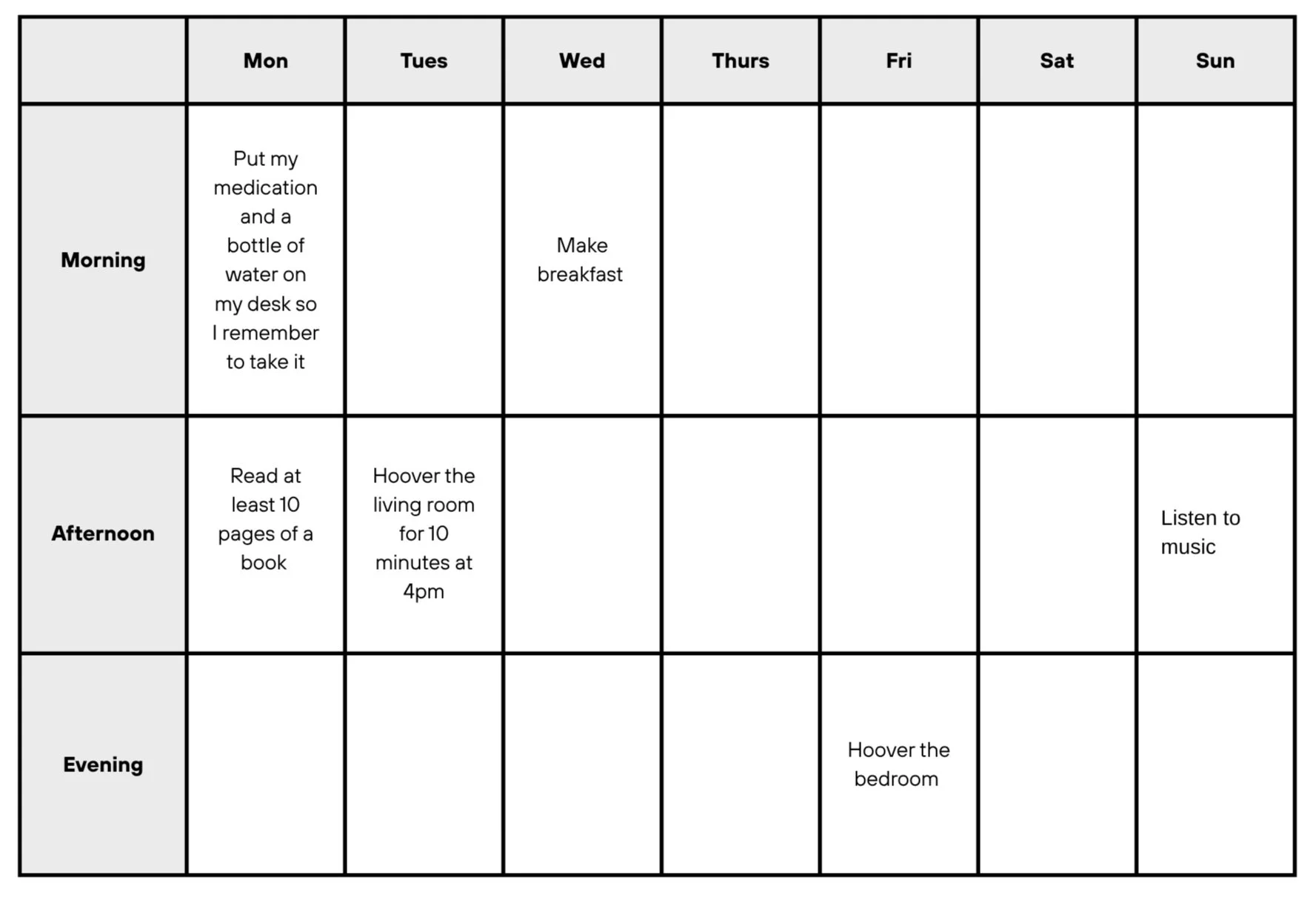

Step 5: Activity scheduling (plan in when these activities will take place):

The next stage is to get the patient to plan in when they are going to do some of the activities. Activity scheduling is central to BA. Most patients already know they need to increase their level of activity and do things. However, when depressed, the majority of patients wait until they feel motivated to engage in an activity. This simply doesn't work, and patients' activity levels gradually reduce over time. Therefore, during BA, patients are encouraged to actively plan in activities and follow through regardless of how they feel at the moment. Patients are advised to follow the principle of “following the plan, not the feeling”.

An activity schedule should be used. There are many versions of activity schedules, which range from hour-by-hour time blocks to more less detailed dairies. Use whatever feels most relevant to your patient.

Rationale for activity scheduling:

When feeling low and lacking motivation it can be very hard to start doing activities. Often, we can intend to start, but following through is hard. Think back on a time when you wanted to start a new diet or exercise program; it was probably easier to plan to start than follow through. We can overcome this lack of motivation by planning our activities in. Start slowly with just a few easy ones and build up each week.

Follow the plan, not the feeling: Discuss with the patient the importance of following the plan rather than how they feel on the day. If the patient follows how they feel, then it is unlikely they will do anything on their list.

Use effective planning in strategies:

Planning in more detail increases the likelihood of the patient following through. Using SMART goals works very well:

Specific: Plan the activity in a very detailed and specific fashion. Consider the four W’s when planning in: What, When, Where and Who.

Measurable: The patient needs to know when they have actually achieved their goal.

Achievable: Start with the easy category.

Relevant: Use a mixture of routine, necessary and pleasurable.

Timebound: There is no point planning most things for a long time away. Plan in for the week where possible.

For example, which of these two plans do you think is more likely to be followed through on?

Next week I will make sure I go to the gym.

Next Tuesday at 10am, I will go to my local gym with my best friend Tom for at least 60 minutes.

Most would argue that number two is better. It’s very specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and timebound.

Make it convenient:

The human brain is wired to find convenient options more desirable. This can be used to BA’s advantage. Ensure whatever activity is planned is easy to start right away. For example, going to the gym requires many steps to start (getting changed, finding your shoes, keys, headphones etc) before even heading out the door. So, the patient could prepare a bag in advance. It is much more motivating to just pick up your gym bag and leave, compared to packing everything before you leave. This convenience also extends to proximity. For example, if a patient wants to replace excessive Xbox gaming with playing their guitar more, then they can place the guitar within arm’s reach of the sofa, and always put the Xbox controller in a far distant room so they have to get it each time.

Here is an example activity schedule with a few tasks planned in:

Step 6: The patient doing the activities:

The next step is for the patient to go away and do the activities they have planned.

Reinforce the idea of “Follow the plan not the feeling”.

Following through is entirely up to your patient to complete. If they have any issues, then troubleshoot and problem solve how to help the patient engage. Consider using your COM-B.

Step 7: Reviewing the patients progress:

During sessions, review if the activities are having an impact on the patient's mood. Ideally the patient has realised they feel better after doing activities. It can also be useful for the patient to start reflecting on their progress after tasks. Some activities will increase mood more than others. They can learn to promote the ones that do and reduce the ones that have little impact. A new activity schedule should be set weekly based on what improves the patient's mood the most. If the patient has any problems or difficulties in which they avoided their planned activity, or did not feel good doing something that should have been, draw out the situation as an ABC cycle, explore barriers, problem solve and plan in it again.

Written by David Kaneria

CBT Therapist & Previous Psychological Wellbeing Practitioner (PWP)

Author of Low-Intensity Cognitive Behaviour Therapy; A Psychological Wellbeing Practitioner (PWP) Handbook

Low-Intensity Textbook:

For more information on Cognitive Restructuring and much more, check out my PWP textbook on amazon.

Patient Depression Self Help Book:

If any patients could benefit from any further support after therapy to maintain their progress my self-help book contains all the step 2 depression strategies in one easy to understand book.